SanDiegoCJ

Non-Lemming

Now it's way too regimented and IMO boring.

Yes they changed all sponsored racing from a Death Match to an actual race to see whose car is the fastest.

I don't like it any better than anyone else. Jackie Stewart can talk about being trapped in his car leaking gasoline and cooked human meat smell wafting over the stands and track as much as he wants, the truth is, he kept going back.

There is no shortage of men willing to risk their neck racing, all racing safety has to do with marginal fans (women) and insurance/tort.

Two days after Sunday’s Canadian Grand Prix, Sir Jackie Stewart, the driver who was instrumental in shaping modern Formula One, will celebrate his 80th birthday: a milestone for the three-times world champion in the year that also marks the 50th since he won his first world title in 1969. The difference between F1 then and now could not be more marked.

Death stalked racing in Stewart’s day and that the sport is relatively safe now owes a huge debt to the Scot. His role in pressing for change is well known, but perhaps less so is the huge emotional toll the deaths inflicted and just how difficult it had been trying to force through better safety standards for drivers.

My friend Niki Lauda was a street-fighter and a shining talent in F1

Read more

Stewart’s F1 career began in 1965. He won titles in 1969 for Matra and in 1971 and 1973 for Tyrrell and retired at the end of that last championship season. He chose not to compete in the final race at Watkins Glen after his friend and teammate François Cevert was killed in practice. He had already decided to retire at that point, but after a career of beating the odds, Cevert’s death was enough to prompt Stewart to walk away from what would have been his 100th grand prix.

He left the track and told his wife Helen “I’m no longer a racing driver”, events he recounts in detail and with much emotion in the journalist and broadcaster Will Buxton’s new book, My Greatest Defeat. It is a fascinating collection of interviews in which a variety of drivers, including Niki Lauda, Alain Prost, Damon Hill, Mika Häkkinen, Mario Andretti and Emerson Fittipaldi talk of the moments that tested them most.

Stewart’s contribution is particularly moving as he remembers the devastating effect of Cevert’s death. Yet he notes with regret the Frenchman was but one of many. He recalls he and Helen counting 57 deaths while he was racing. Many were close friends. “So many people were killed during that period,” he says. “Jochen Rindt was killed, Jim Clark, François, Piers Courage – and in those days they never stopped the race. You kept racing.”

That they did so was entirely normal at the time, but it did not make it any easier to cope with. Rindt died in qualifying for the 1970 Italian Grand Prix, but Stewart carried on. “I was crying when I went into the car because I was with him when he died,” he says. “Ken [Tyrrell] had said to me: ‘Listen, you’ve got to go out’, and I burst into tears in the car. But I went out and I did the quickest lap I’d ever done at Monza at that time. But I got out of the car and I burst into tears again.”

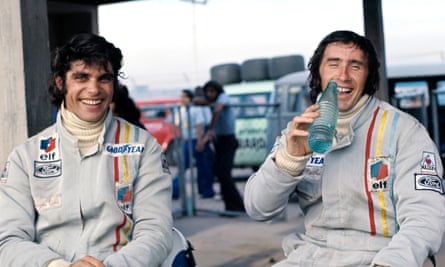

Jackie Stewart with François Cevert, who was killed during practice for the final race of the 1973 season at Watkins Glen, New York. Photograph: Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Nor was it only the drivers who had to deal with the relentless death toll. When Clark was killed at Hockenheim in 1968 he was the first of four drivers to die in consecutive months. The wives, too, had to shoulder some of the hardest burdens.

“They had a circle called the Dog House Club where they’d all go and have cups of tea when we were with the engineers,” says Stewart. “Bette Hill, Helen and all the wives all together. When one of the drivers was killed, all the other wives had to look after each other. Helen had to look after Nina when Jochen was killed, Sally when Piers was killed – and she looked after me, too.

“But to have to go and pack the bags of somebody who had just been killed, because their wife couldn’t stand to go back to the hotel room, well, Helen had to do that so many times. She went with so many of the wives to the hospital, helping them all in their moment of absolute grief. She was so strong.”

Jim Clark, the indecisive farmer who was transformed behind a wheel

Read more

Nowadays, Stewart battles on Helen’s behalf with his Race Against Dementia charity, seeking to deal with the disease that has afflicted his wife. He has never backed down from a fight.

Prompted by the accident at Spa in 1966 that left him for 25 minutes upside down in his car soaked in fuel, Stewart campaigned robustly to improve safety. For run-off areas, better barriers, advanced medical facilities, proper marshalling; he led boycotts of races at Spa and the Nürburgring. His work was not welcomed, but was ultimately successful. F1 has had one race-related driver fatality since Ayrton Senna and Roland Ratzenberger were killed in 1994.

Stewart’s legacy was hard-fought, but is, to an extent, unrecognised. “My quest for safety had become by far the most unpopular thing that I was faced with,” he says. “I don’t think there’s a single corner of any race track in the world called Stewart corner. The organisers, the governing body and the track owners were so angry that somebody who happened to be the world champion was saying that we were not going to race at the Nürburgring or Spa.”

His account reveals the very human and very tragic side of what racing entailed in the 60s and 70s and in doing so illustrates his role in changing it for ever. It seems extraordinary that when Stewart reaches 80 on Tuesday there is still yet to be a corner that bears his name.